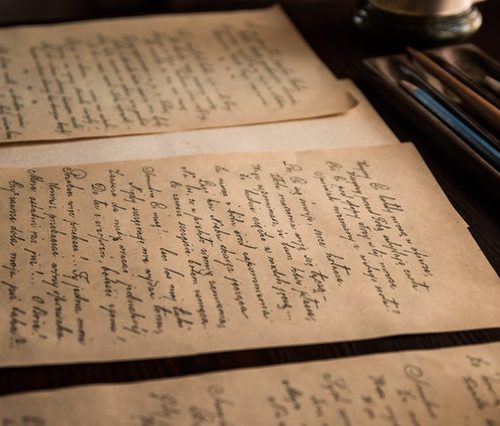

Dusty manuscripts and half-burnt newspapers

As a writer, one of the most valuable skills you can learn is how to sound like yourself on the page. It’s easy to worry about sounding ‘proper’, or ‘writerly’, and to go on to write unnatural prose. But sounding like yourself isn’t always the effect you want to go for. Your narrator might be completely different from you, for instance, or they might be unreliable. Recently I’ve been thinking about poems and novels which avoid putting a first-person ego centre stage. In my next two blogs I’m going to suggest a couple of ways in which you can explore different voices in your writing. These are fun exercises which might take your work in interesting directions.

Here’s my first suggestion: embedded documents. There are various technical terms for these, but for our purposes an embedded document is a made-up piece of writing which is inserted into a piece of fiction, and which has a different voice to the main narrative. For example, in Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, Holmes and Watson have an eighteenth-century manuscript read aloud to them by another character. It’s also reproduced on the page for the reader. The manuscript explains the origins of the ‘Curse of the Baskervilles’ and the hellish hound which is said to haunt the Baskerville family. This embedded document is a great way for the author to introduce information without requiring characters to engage in a long and boring conversation. It also provides a story within a story, and Conan Doyle can indulge in a more Gothic style, with archaic words and hints at the supernatural which are a world away from Sherlock’s rationalising. Sherlock, it should be said, distrusts this crusty manuscript.

The idea of embedding a document into the narrative has been a hallmark of Gothic horror for over two hundred years. Characters in eighteenth-century Gothic novels are always finding mysterious manuscripts in old chests, hidden in the corners of dusty cellars, and these manuscripts are ‘reprinted’ in the narrative. In a more recent novella, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, a series of letters reveals the sinister secret of Jekyll’s split persona.

Why do Gothic horror writers often embed documents? Because these novels are concerned with truth. They make us ask if we can always believe the evidence of our senses. They suggest that superstitions might explain events which are beyond scientific enquiry.

When you invent a document and embed it in a piece of fiction, the reader is left to work out which piece of text – the document or the wider narrative – is reliable. Embedded documents are a way of playing various versions of events off each other. The sense of uncertainty can be ramped up even further with ‘found documents’ – embedded documents which aren’t written by the author, such as genuine newspaper articles.

Embedding documents isn’t just a Gothic trope. In his novel satirising 1980s British politics, What a Carve Up!, Jonathan Coe embeds two newspaper articles side-by-side: they look like newspaper clippings which have literally been cut and pasted on to the page. Both are written by the same character, a notorious newspaper columnist. Each completely contradicts the other, so that the overall effect is that neither column is trustworthy, and the columnist loses all credibility.

Here’s an exercise which will enable you to experiment with this technique. Imagine you’re a journalist, and write an article reporting on an imaginary incident. Or, for a different approach, scour a newspaper for a column that interests you. Once you have this piece, imagine a character coming across this article. They might read it on a noisy bus. They might be attracted by the headline on their way to a wedding. The might discover its charred remains in a fire grate, or find it wrapping their fish and chips. Write the narrative surrounding their response to the article. Do they agree with it? Can they produce a second document which disproves it? Write this as a story, remembering to quote the article in full in the middle of it.

Image of papers free to use from Pexels.

|

|

Brilliant!

My character finds a message in a bottle – a newspaper cutting about a murder.

Under the cutting, in pencil, is written: “I didn’t do it. Tell them.”

How does the finder react?

Thank you for such intriguing prompts. I’m interested in incorporating play scripts into my life writing – I think your suggestions can enrich my approaches to how I might do this. Your comments also make me think about whose voice I will be writing the play scripts in – my own, or …?