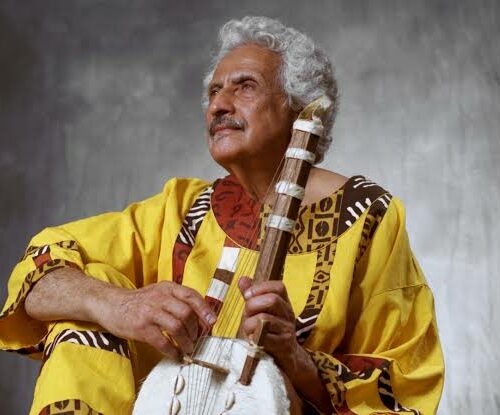

Electronic Music 1 – Halim El-Dabh

In 2023, I ran a Listening Group session with OCA students, focused on electronic music. There was quite a lot of enthusiasm for the ideas we discussed and, consequently, I have decided to write a series of blog posts exploring the history, techniques, and aesthetics of this beautiful and bewildering type of music.

Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry are certainly important figures in the history of electronic music, credited with the development of musique concrète (concrete music) in the 1940s, which focused on assembling and manipulating recorded sound. I will write about both Pierres in future blogposts (perhaps, multiple times), but I have decided to focus the first blogpost on Halim El-Dabh; a remarkable innovator, often overlooked, who composed one of the very first pieces of musique concrète.

El-Dabh was born in 1921 in Cairo, Egypt. While studying Agricultural Engineering at Cairo University (then known as Fuad I University), he began experimenting with magnetic wire recording and, in the early 1940s, used that technology to record the sounds of a Zaar ritual.

In African countries (particularly those in the Northeast of the continent) and nearby Middle Eastern countries, the word Zaar is used to describe spirits that possess people. The exact nature of the spirits varies significantly from region to region, but they often bring illness or discomfort to any who are unlucky enough to be possessed. Rituals are undertaken to appease the spirit, and involve music, dance, and food. El-Dabh used a wire recorder to capture some of these ritual songs, and transformed them into an early example of musique concrète composition, called Ta’abir al-Zaar (which translates as The Elements of Zaar). Originally a 20-25 minute piece, the two minute sample below is often referred to as Wire Recorder Piece, rather than Ta’abir al-Zaar.

I think this is an astonishingly beautiful work, and, given the limitations imposed by the recording/mixing equipment of the 1940s, genuinely ahead of its time. In using the technology that was available, El-Dabh displayed, in my opinion, remarkable inventiveness and experimentalism. For example, he describes using movable walls in a studio to create different types of reverb.

Fast-forward to 2024, and experimenting with reverb (and other effects) is so much easier than it was in the 1940s. You can try this yourself, if you wish. Downloading Audacity on to your computer will allow you to manipulate sound recordings. In many cases, to get started, the in-built microphone on your laptop is good enough, as are the microphones on many mobile phones. A good, multipurpose dynamic microphone (like the Shure SM57) can be bought for approximately £100 (but will also require an interface), or you could use what I use; a Zoom H6, which is a portable recording device with in-built microphones. For approximately £200, I have a stereo microphone setup that I can take anywhere. Unlike El-Dabh’s experience, which required the use of rerecording rooms and movable walls, we can add reverb to recorded sound with a click of a button. (Although, I would argue, convenience is not always conducive to creativity; and composers often find beauty in restriction and limitation).

The other thing I find so captivating about El-Dabh’s piece is that, through filtering of the recordings, he makes the recorded voices sound more ambiguous and otherworldly. This composition is not an accurate depiction of what a Zaar ritual sounds like, but it goes deeper, perhaps reflecting what it feels like to witness one of these ceremonies or, even, what it is like to be possessed by a Zaar.

I feel a real affinity to El-Dabh as a composer; I am captivated by any electronic piece that incorporates human voices. Like El-Dabh, I enjoy manipulating voice recordings so that the words are no longer audible (but the characteristics of the human voice are still present).

In 1950, El-Dabh was awarded a prestigious Fullbright fellowship to study in the US. He later received a PhD from Kent State University, where he then taught for over 40 years. He died in 2017, at the age of 96, having lived an absolutely remarkable life. He engaged in extensive ethnomusicological research (concerning a range of countries/cultures), and received many awards for his composition and academic output.

Here is El-Dabh discussing his score for the ballet Clytemnestra, choreographed by Martha Graham and premiered in New York in 1958.

For more information, you can visit the official website of Halim El-Dabh http://halimeldabh.com/ and read Electronic and Experimental Music, an excellent book written by Thom Holmes (first published in 1985, with a sixth edition published in 2020). Holmes interviewed El-Dabh in 2007, and the book details some of the composer’s practices and preferences.

|

|

A really interesting article, Ben! The layers of sound and how they’re put together to communicate fascinates me. There’s no end to the creativity that can be accomplished when working with sound. The wire recorder is awesome isn’t it! Apps and programmes for experimenting with sound are so readily accessible now. Some great recommendations here – thank you.