To plot or not to plot

Plot is possibly one of the most overlooked aspects of scriptwriting: coming up with the right idea, developing complex and captivating characters, creating a structure, building conflict are usually every writer’s priority, before sitting in front of the screen and starting to type.

And when plot comes into question, there is often a misconception about what it is and how important it is for the completion of the script.

PLOT AS METHODOLOGY

Imagine that you want to go on a trip somewhere: after deciding the purpose of it and the final destination, you start planning how to get there and what to do when you arrive. Come the moment of departure, you go through a series of smaller events (leaving your house, phoning a taxi, getting to the airport, buying yourself a nice meal while you wait for your flight to be called) that eventually take you, step by step, to your final destination. Each small event is either instigated by you or happens to you, provoking your reaction.

Now imagine that you want to go to that same place, but you simply decide that it doesn’t really matter how: you just get up from your chair and after a few acts of minimal preparation, you lock your house door behind you and see where your instincts take you.

Perhaps a bit extreme but these two examples encapsulate a dilemma: which one of these two trips is easier on the traveller and will turn out to be more successful?

A script is not a journey just for your character, it’s a journey for you as the writer and, when it comes to structuring your story, plot is very often one of the hurdles that makes a writer feel stuck and suddenly empty of any creative sparkle. After much brainstorming on the classic 3-act structure, you have a beginning and you have figured out how your story will end but what goes in the middle feels like a titanic job. Could you just start writing the beginning and the ending, and work out your way there as you write?

Quite similarly to travellers, there are writers who plot and plan each step of their story in a meticulous fashion (using beat sheets, outlines, index cards) before embarking on the actual writing phase and there are writers who believe in the “go with the flow” approach because it feels somehow more creative and artistic.

Given the technical nature of a script, there is a strong argument for favouring the former approach; as you can’t exceed the 120 pages limit, within those 120 minutes you need to take your reader all the way to an ending which is emotionally and dramatically connected to the beginning. This implies including a series of events that move the story forward in a cause-effect logic. Basically, an order of events that are either driven by your character or happen to your character (triggering his/her reaction) according to their core goal.

Your story follows a direction and plotting gives it the focus towards that.

Does this mean that once you’ve planned the chain of things happening in your story you have to stick to them through to the ending? Not necessarily. A script is a work in progress that can (and indeed, should!) always be modified and reviewed; it is a product of your imagination, therefore new ideas, new plot points, even a different ending are welcome.

However, following your instinct and starting writing without even an approximate idea of what narrative itinerary you are going to follow, can make you waste a lot of time and energy and, possibly, lose the focus of what story you are trying to tell.

Once you are clear about what your story is about and what your main character wants, perhaps the best way to tackle the plotting phase is by using index cards in a progressively expansive way: starting from three cards for your beginning (B), ending (E) and central turning point (TP), you should aim to add two cards – one between B and TP and the other one between TP and E. Keep adding cards, as if you were adding building blocks to a bridge: at each step, ask yourself what needs to happen for your character to reach the next check-point and make sure that the core of your story and your character’s drive still hold together.

PLOT AS THE ‘MEAT’ OF A STORY

In order to write a whole script, you certainly need lots to happen, with a constant sense of progression towards the end. Or maybe not? How much plot do you need?

VLADIMIR: We can still part, if you think it would be better.

ESTRAGON: It’s not worthwhile now. (Silence.)

VLADIMIR: No, it’s not worthwhile now. (Silence.)

ESTRAGON: Well, shall we go?

VLADIMIR: Yes, let’s go.

They do not move.

Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1953), that was adapted from stage to screen several times and most recently in Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s 2001 film (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YuxISg9tjHk) is an example of a masterpiece that has no plot in the classic, beginning-middle-end, meaning of it. Two men wait. They sit in the middle of nowhere and…wait. They pass the time discussing whether they should wait or not. They wait a bit longer. When they resolve to move in the end, they do not move.

There is no plot because, amongst the several different interpretations given through the years, the play’s obsession with immobility and waiting can be read as an existential reflection of the stasis in which all our lives really are: we always wait for the next thing to happen, sometimes we don’t know what, and we live off expectations without real agency.

Terrence Malik’s The Tree of Life (2011, download the script here: https://indiegroundfilms.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/tree-of-life-the-jun-25-07-1st.pdf) revolves entirely around a man’s childhood memories, capturing moods, feelings and moments without a properly plotted story. Why? The film wants to be an experience, a visual reflection on human life, nature and spirituality. It doesn’t need a traditional plot to deliver its dramatic and emotional message to the viewers.

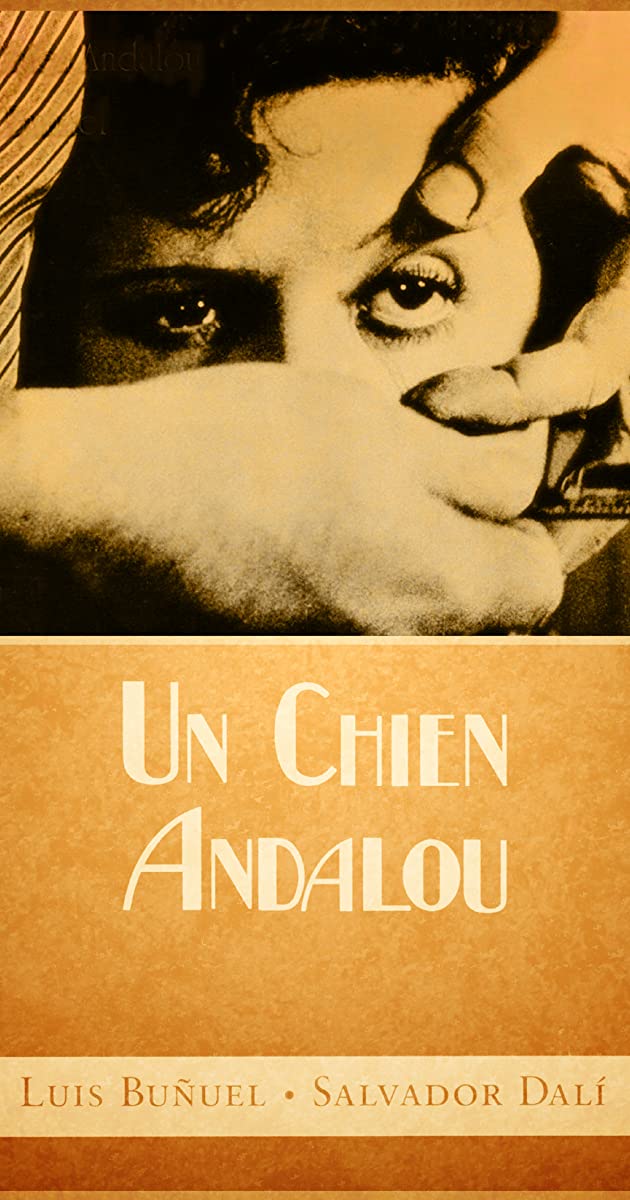

With the exception of serial TV where plotting is essential to episodic structure, there are numerous stories for stage and screen (mainly independent films) that don’t rely on a forward-moving narration, or even on a causal one: take, for example, The Square (2017) where things happen but are not necessarily related to one another in a logical, progressive way, or art films such as the alienating Un Chien Andalou (1929, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cB7gd_t6WMQ), or classics such as 12 Angry Men (1957), where the unity of location turns into a heavy use of dialogue and not much movement.

But if you think carefully about any story where characters don’t do much and/or don’t do it within a hero’s-journey narrative arch, as long as you have a story, plot is there, even when it’s not linear, causal or evidently dramatic.

Whatever is happening on screen or on stage is the plot, to various degrees: from the formulaic, Hollywood-style, strictly consequential and goal-driven plot, to the minimalistic, surreal, abstract narration of the examples above.

So, when you come to plot your script, perhaps the question you should ask yourself is whether your story is better told with a traditional approach to plot or not.

And if you opt for a minimal or unconventional plot, make sure that it is justified by a creative choice that is in line with what you’re trying to tell with your story.

The decision should be a conscious one, because non-traditional plotting is as complex to master as the classic one, if not more.

Featured image: Source: pexels.com

|

|