OCA Fine Art: Call and Response

In March this year I was asked to host the first Call and Response session as part of BA (Hons) Fine Art group work, to look at different venues and collections around the world that were perhaps lesser known in relation to the different degree programmes offered at the OCA. At this point in the pandemic, many of us were in lockdown across the world, and this offered a chance to escape to look briefly at the collection and digital presence at The Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) in Miami, USA, dedicated to collecting and exhibiting International Art of the 20th and 21st centuries from the Americas, Western Europe, and Africa. As well as looking at and discussing the PAMM collection, there was a particular focus to the Call and Response session, to look closely at an exhibition by the artist Ebony G. Patterson titled ‘while the dew is still on the roses’ held there in 2019.

Known for her drawings, tapestries, videos, sculptures, and installations that involve surfaces layered with flowers, glitter, lace and beads, Ebony G. Patterson’s works investigate forms of embellishment relating to youth culture within disenfranchised communities. Her neo-baroque works address violence, masculinity, bling, visibility, and invisibility within the post-colonial context of her native Jamaica and within black youth culture globally. For her exhibition at PAMM, Patterson focuses on the role that gardens have played in her practice, referenced as spaces of both beauty and burial; environments filled with fleeting aesthetics and mourning. It is clear in researching more around the work itself, through her making, Patterson is commenting on the raising of identities of the marginal in society, particularly black youth culture and its place in society both in America and elsewhere. Her work encourages more critical ways of looking at 21st century social and cultural issues by interpreting the value and meaning of what we are seeing.

In her artist statement Patterson explains

“My work often explores working-class cultures and spaces, and the engagements in declaring presence as an act of protest. I aim to elevate those who have been deemed invisible/unvisible as a result inherited colonial social structure, by incorporating their words, thoughts, dress, and pageantry as a tactic to memorialize them. It is a way to say: “I am here, and you cannot deny me.”

To give context to territory, human value, and demarcation at this point across time, in 1899, the British colonial administration in Jamaica passed a set of legislation known as the Public Gardens Regulation Act. Designed to organise the maintenance of public spaces throughout the island, the act established a framework of policing and punishment on “any land maintained at public expense.” The act proclaimed that officers could seize stray animals found in the gardens and allowed officials to stand in for garden employees as “Special Constables” who could take these offenders into custody. At the same time as the colonial garden was part of an elaborate performance of property and order, gardens of another kind abounded throughout the island. As the novelist Olive Senior notes in Patterson’s exhibition essay, provision grounds, kitchen gardens, and yards all served as domestic spaces for poor and rural families to cultivate their own crops.

In varying ways then, the Jamaican garden has been a contested terrain, from a closely monitored public resource, a private space of nourishment, a site of portraiture and a place of aspiration. Like the Jamaican garden itself, and like the labouring bodies which brought it into being, Patterson’s collages are left marked, are multiple in number and left unravelled by the layers of history and meaning that they appear to carry.

Patterson’s works are weighted with paper hanging down in thin shreds, butterflies and birds stretching into a third dimension, jewellery and ornaments gleaming amidst the ruckus as if they were on a street vendor’s table perhaps in Kingston or in Flatbush. The landscapes and flowers are dotted with small ruptures, circular cut outs which expose the gallery wall behind. In some areas, fragments of faces are visible: an upside-down forehead and eye, a lip, trailing off into strings and vaguely organ-like shapes. The longer we stare, the more we find. A purse is visible, and now a snake. A pair of leopard print shoes slowly makes itself known. A gold costume necklace glints above the plants. The effect is distressing, exhilarating, a calculated confusion of beauty and dismemberment. While the gardens so carefully maintained by colonial administrations may have been meant as a kind of analgesic for the horrors of plantation slavery, Patterson’s gardens don’t lie to us about mortality. They never quite obscure the death and loss which brought them into being.

From the disembodied faces and limbs to the wounding and puncturing which echoes throughout the pieces, Patterson’s gardens are not places of leisure, but of haunting. Elsewhere, the artist has spoken of drawing from newspaper crime scene photographs in her earlier “Dead Treez” series, placing these symbols of public spectacle and voyeurism within unruly garden landscapes. In the pieces shown at Hales Gallery in London also in 2019, there is still no intact body, only fragments, continual whisperings. At the same time, Patterson draws on the ornate visual language of Black femme self-adornment and dollar store ritual that have become signatures of her work, reminding us that for some, prettiness exists in constant negotiation with violence.

Ebony G. Patterson often references the writing of Olive Senior, in particular her poetry titled ‘Gardening in the Tropics’. Born in rural Jamaica to farmer parents, Senior is well known for re-inhabiting and recreating the wonder and cruel theatre of childhood across her career in writing, where she has negotiated race, religion, politics, and history after colonisation through her references to nature. Senior’s recognition of the beauty and entangled menace just beneath the surface of Caribbean landscapes is useful as a framework for thinking critically about how Caribbean artists appropriate neo-colonial tropes of landscape in their aesthetic practices. Long providing the backdrop for slave revolts, labour riots, romances, fantasies and nightmares, the metaphor of the garden highlights the historical lessons that are buried in Caribbean flora and fauna, making the garden a curiously pedagogical space.

Her gardens are not simply or purely ornamental, they include sugar and plantations, jungles filled with life sustaining weeds and plants, large trees that provide shelter as well as weapons of resistance.

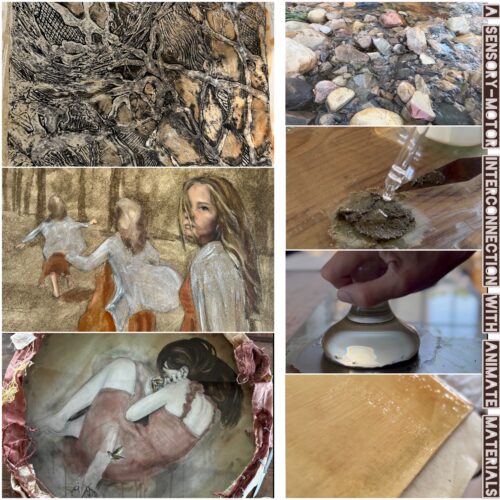

And so, taking a tour around her work and discussing how she uses beauty as a tool to entice as well as capture her audience, students were asked to bring in their own collection of things, from objects to materials, to pursue your own ideas around demarcation. You will see various activities from within this session on the Padlet link below as well as some feedback from a couple of students in this session.

https://oca.padlet.org/hayleylock_tutor1/ftrmdk83fq0ud5ip

Student feedback from the session

“I wanted to learn in a group setting and researching prior to the session was brand new to me. By looking at artworks I usually would not look at, I think about things I usually don’t think about, and realise things that I always know but haven’t expressed openly to many. I came out of my comfortable bubble and voiced my anger and frustration. And this might open up a new thread of investigation for my future study. “

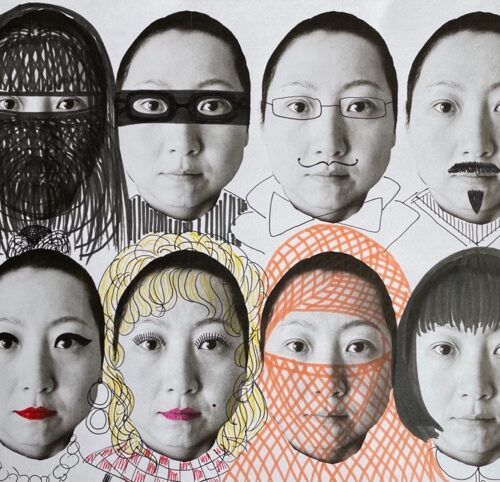

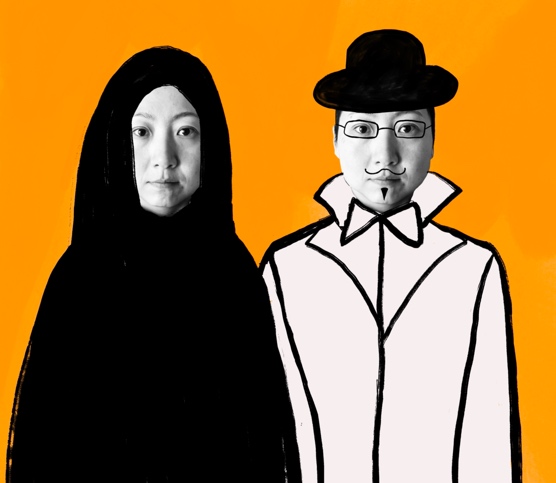

I believe some of my collage works were inspired by things I thought about due to this session.

Han Qin, 8 March 2021

“Community is so important to any artist’s practice, especially to the student artist. Community exposes the creative to new perspectives, new ways of thinking, new practices, new cultures, work and galleries that they may not have searched out. Community is an important pillar of any artist’s life.

Building community is something that OCA does very, very well. The advent of a global pandemic didn’t in any way hinder OCA’s already extensive experience in delivering remote learning: if anything, it stimulated a growth response, more online workshops, more talks, more opportunities to connect.

And community was one of the reasons I wanted to take part in this session. Relatively new to OCA’s BA in Fine Art, this Call and Response session was my first opportunity to connect with other students, and other Tutors, to share ideas and new perspectives, to be influenced by something other than my own thoughts and research. The focus of the session was also a massive draw. In the first few months of my studies, before this session, the research I was being encouraged to do in ‘Exploring Drawing Media’, was exposing me to artists and practices that I would never have known to consider. Hayley’s session offered the promise of further expanding my horizons with a deep dive into a collection I never knew existed, a personal investigation that would be shared and discussed with other students – and a professional artist.

But being led through Ebony G. Patterson’s work by Hayley and being able to discuss it with fellow students was a revelation for me personally! The session became an opportunity for me to delve past the visual aesthetic of Patterson’s pieces, to recognise what she was communicating and the materiality of how she was having that conversation. I was being challenged to see beyond the surface of the work and think about how and why it was created. I was being asked to see the work, not just look at it!

And then the ‘Response’ phase of the session, when I very much felt like a rabbit caught in the headlights. I had my ‘things’, but how could I use them to address the theme of demarcation we had been set? How were these objects representative of my experiences, my identity, my community? Discomfort is a useful place for an artist to inhabit. It offers the challenges a creator needs to move forward. And the discomfort did so for me. The beginnings of an idea surfaced, unconsciously triggered by the prior content of the session. My mind tenuously related the concept of ‘Demarcation’ to my relationship with my home town, the physical and emotional boundaries this wraps around me. My place within the boundaries of the town. This is the place I was born, a place I wanted to escape from, and yet, despite my travels, I have kept returning, and discovering new and delightful opportunities. I also want to subvert relationships of scale – at the time of the session, we were all inside these small boxes (zoom) at the moment, in our homes in our town. I started to think about how to bring the town into Zoom, the large into the small. I have started with a drawing, an unlabelled map of the main roads that run through and around the town, on to which I populated sketches of the objects I had brought to the session.

At the culmination of this session, though, I realised that there had been a fundamental, albeit small (at the time), shift in the way that I thought about art objects. From previously looking only from a surface perspective, I had been introduced to a level of critical appraisal that required understanding as well as seeing. It was at this early point in my studies that I had started to recognise the virtuous cycle that leads from truly seeing to understanding and understanding to truly seeing, and, how underpinning that, being part of a community helps those skills to develop in me”.

Nikolas Head

|

|