Music and Maths 4: Probability and Composition

In the last blog post we looked at how strict processes can be used in composition, taking examples mostly from minimalist composers. In this post we’ll be looking at a more open-ended type of process: probabilistic decision making.

In the process music we looked at last time, each rule had a single possible interpretation, exactly defining what happened at each stage of the piece – this is called a deterministic process. In contrast, a probabilistic process, rather than defining exact outcomes, defines the likelihood of a given result in any given circumstance.

To give a simple example of how this might work in practice, let’s take the white notes of the piano keyboard as our domain, and say that, starting on the C above middle C, there’s a 50% chance each note will go up in pitch by one step, and a 50% chance it will go down.

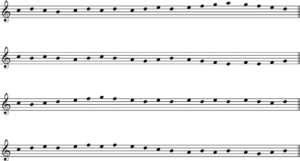

Here are four implementations of this rule, each 20 notes long. As you can see, they are all different, so couldn’t be produced by the same deterministic process. By invoking probability, we can use the same process to produce a range of different but related material.

As with the basic demonstration of process music we came up with in the last post, there’s nothing particularly exciting about our example. However, by using more creative and sophisticated rules it’s possible to create dynamic and intricate musical material using this sort of process.

In the first section of my piece oiseaux métamorphique for recorder and electronics, I exploit contrast between deterministic and probabilistic processes. The tritone oscillations and rising arpeggios which open the piece return in a strict numerical cycle, while the more rhapsodic, melodic material between them is generated from probabilistic runs up and down the harmonic series over different fundamentals (the harmonic series is adjusted to conform to the chromatic scale – there are no microtones). This sounds complicated, but is really a very simple process, as I explain below. There is also another probabilistic process at work, in the electronic resampling of the recorder.

This is how a phrase would be generated using a probabilistic process:

- Take a given starting note, say A.

- Randomly determine a fundamental which the A could be a partial of, say a low F, of which our A is the fifth partial.

- Randomly choose the number of notes which will form this part of the phrase, from within a set range, say five.

- Continuing the up the harmonic sequence of the low F for five notes gives us this phrase:

The process then repeats, but with a descending phrase:

- The starting note is now the final G of the last phrase.

- A new fundamental is generated, this one is a low C, of which the G is the 12th partial.

- A random number of notes is chosen, this time seven.

- In alternation with the previous one, this phrase descends, to give:

Iterating the process a few more times gives a longer line:

While this leads to interesting and potentially unexpected routes through a series of (approximately) major scales and arpeggios, there’s nothing here which couldn’t be composed intuitively. One of the big advantages of using processes like these is in the composition of multi-part textures. For example, in the extract below, from my viola concerto Void-Song, the strings begin with a texture of short notes, randomly chosen from a fully chromatic set, and undergo a gradual transition to long notes randomly chosen from a harmonic series on E-flat. (The winds play a pedal on E-flat, articulated in a lengthening numerical sequence.) It’s quite a striking effect which accesses the potential of the orchestra as a massively multi-part ensemble.

Using processes like these to create multi-part textures which share characteristics but vary in details is a powerful addition to the composer’s toolbox. Creating complex, dense or detailed textures “by hand” is a long and time consuming process, which can easily go wrong. Using a probabilistic process can give, paradoxically, more control over these aggregate textures, as it ensures consistency in a way which can be hard to achieve without strict guidelines.

There are tools out there which can be used to realise this sort of process via MIDI – pure-data, openmusic and MaxMSP, to name a few. However, it’s entirely possible to work them through by hand, and in a way this gives you more insight into the detail of what you’re doing.

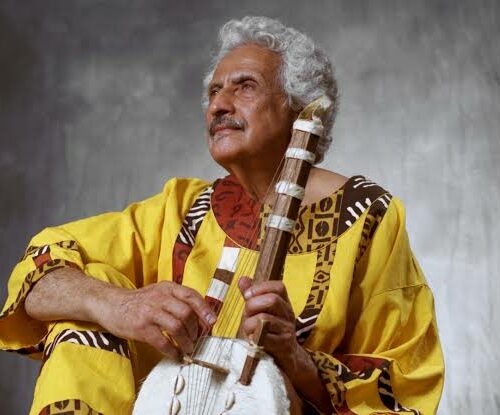

Composers who have worked with this sort of tool are often in the modernist or avant-garde vein. The most famous proponent of probabilistic, or stochastic, music was Iannis Xenakis, who used mathematical tools to create sounds and textures far outside of the conventional western musical language. Here are a couple of pieces which illustrate the power and vibrancy of this approach:

However, there are plenty of ways of using process based tools in less confrontational contexts. A beautiful example of this is the online installation Listen to Wikipedia, from Hatnote. Live data on article creation and editing is pulled from Wikipedia, and used to create an ever-changing soundscape. This is not only an attractive piece of sound art, it connects the listener in a very real way to the wider world.

Once we start thinking of music in terms of the principles which govern the durations, pitches, dynamics and so on which make up a “piece”, rather than just those things themselves, the possibilities of composition expand, and new ideas of how sound can be shaped into music begin to suggest themselves.

|

|

I loved the article – I recently suggested to a friend of mine, who is musically well trained. and accomplished as music teacher and choir master, that we collaborate with my drawings/paintings I do in reaction to my daily walking practice. I am blown away by the ‘new sounds’ in the hatnote composition. Is it an ongoing process – installation that continues, and when one listens in, is it in that moment?