What is your tutor up to? – Garry MacKenzie

On Long Poems, Mountains and Red Deer

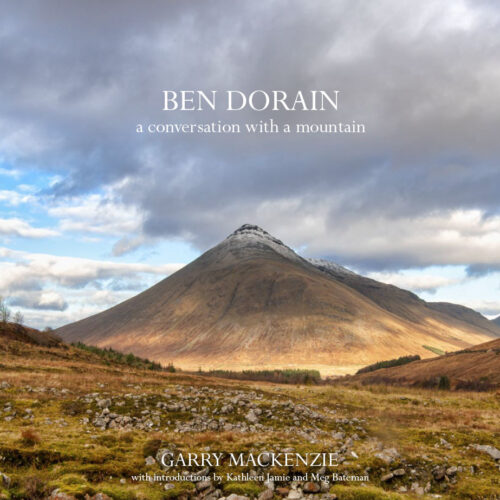

In some of my previous blogs I’ve explored writing about the environment, translation, and building on other texts in your own writing. These are all issues which I’ve been thinking about for my poetry book Ben Dorain: a conversation with a mountain, which has just been published. In this blog I’ll explain what the book is about, and share what I’ve learned from writing it.

Ben Dorain is a mountain in the Scottish Highlands. ‘Ben’ means mountain in Gaelic, and Ben Dorain is the subject of a poem often described as one of the masterpieces of Gaelic literature, Duncan Ban Macintryre’s eighteenth-century In Praise of Ben Dorain. What I love about the poem is that it demonstrates an early kind of environmental awareness. Its eight sections describe the ecological richness of the mountain in wonderful detail, focusing particularly on the life cycle of its herd of red deer. Macintyre’s deer run across the hillside, and can be heard barking and bellowing. They wallow in the mud, and joust in rutting season. The description is unsentimental and precise, like a biological field study: the hill’s deer, rocks and trees are not symbols or metaphors, but deer, rocks and trees.

I decided to produce an English-language translation which would bring In Praise of Ben Dorain to a wider readership. I wanted to do justice to the vitality of Macintyre’s Gaelic poem. Rather than creating an English equivalent of his poetic form – an intricately- structured combination of metre, alliteration and rhyme – I was keen to explore how a completely new arrangement might complement the space and light of the mountain Macintyre describes so vividly. Rather than writing in regimented, consecutive lines, my version includes a lot of white space. Some sections are in prose; others are closer to concrete poetry. A stream is described in words which meander down the page, while playful calves are evoked in words which leap around the page.

My poem is not simply a translation, but incorporates Macintyre’s poem into a new, longer work. Each page of my poem is divided vertically down the middle, with my version of Macintyre’s poem on the left and new material, written by me, on the right. About half of my poem is my version of Macintyre. The rest is my response, which includes contemporary research into deer behaviour; ideas about ecological interconnectedness and deep time; reflections on forestry, gamekeeping and tourism; and commentary on Highland land ownership today. My aim is to bring Macintyre’s poem into the twenty-first century, by putting it in conversation with ideas from our own Anthropocene age.

Working on Ben Dorain has got me interested in how an older poem can be sampled, altered and embellished in order to make something new. When people discuss poetry, they often highlight poems which are forms of self-expression, in which the poet tells you about how they see the world. This can be a fruitful, and sometimes politically necessary, approach to poetry. But it’s not the only thing that poetry can do. In my poem, I wanted to avoid intruding too much on the other creatures which inhabit the mountain, from red deer to peregrines to liverworts. For those of you writing poetry, don’t feel you have to be restricted to one kind of poetic voice or mode: poems can be all sorts of things, and can be structured in all sorts of ways. I found it liberating to experiment, rather than to stick to a single form. If this experimental approach appeals to you, you’ll be interested in OCA’s recently updated Level 2 Poetry: Form and Experience course, which encourages you to try out new forms, to take risks, and to play.

Writing Ben Dorain has also opened my eyes to the benefits of engaging in a long, thematically-linked project. It can be hard to write a collection of short, standalone poems: every time you sit down at your desk, you need to reboot and come up with something new. Sequences, long poems and collections exploring a single theme from a variety of angles are ways round this difficulty. For two years I found that my brain was always turning to the long poem I’d never quite finished, and I was always experimenting with how new ideas might be incorporated into this larger project.

I’ve written more extensively about Ben Dorain in an online article, Ben Dorain: an ecopoetic translation and a recording of me reading sections of the poem is available on the website of the Crossways Festival. For now, let me leave you with a challenge. Have a look at some long poems (Long Poem Magazine is a good place to start!) and poetic sequences. The next time you sit down to write, think about whether your subject could be examined expansively, in a multi-section poem or sequence, rather than in a self-contained single-page poem. I found working on an extended project changed how I thought about writing poetry, and I hope you will too.

Ben Dorain cover used with permission of Irish Pages Press

|

|