In conversation with: Drawing degree tutor Simon Manfield

The Drawing degree is a lively programme with a really great bunch of students. The assessment events for drawing are the place where I as Programme Leader get a chance to see the programme laid out. So far each event has been particularly impressive with students really getting onto all the nooks and crannies of what drawing can be, from a guided derive to a delicately traced still life. The broad and experimental character of the drawing degree is supported of course by the curriculum, and a big part of that is the lovely new drawing degree unit called ‘a personal approach to drawing’ (DR5PAD), so I am delighted to have a chance to have a conversation with one of its authors, Simon Manfield, about his practice:

ED: Hello Simon, I was so impressed last time we met when I happened across your amazing book of drawings illustrating the Impromptus poem by George Mackay Brown. They have a very coherent atmosphere; I felt totally drawn into that wet and moody world which I know well from my time living in the Hebrides. It did make me wonder on a practical level – do you work on all the drawings at once to ensure the mood stays the same throughout?

SM: Hi Emma. Thanks for your question and for your kind words. I can’t really take all the credit for presenting what you generously describe as the “coherent atmosphere” of the Orcadians: Seven Impromptus series of drawings. I was in large part led by the beautiful (and atmospheric) words written by the poet George Mackay Brown. The mood I illustrated was helpfully already described, in black and white, in Mackay Brown’s poetic sequence. To answer your specific question on my working timetable: quite the opposite, I spent roughly eight years on that series of sixteen drawings, including the various preliminary versions for each impromptu while immersing myself in the poem. Interestingly, out of the seven impromptus the one that tested me the most was the shortest, Chicken, which is only twelve lines in length. This was not due to a dearth of inspiring pictorial language but the reverse; it is so succinctly crafted, so visual in its description, that it offered a plethora of visual possibilities!

I would say though, like your time living in the Hebrides it did help that after many visits I knew Orkney well enough; the character of the archipelago, its seasons and its landscape.I also have very good and dear Orcadian friends which assisted in the characterisation of those inhabiting the sequence of poems.

ED: I think that says something very interesting about pace and how it affects work. I make work which takes hardly any time, and sometimes feel a kind of urgent need to quickly fashion something just to see it and quieten my brain, but equally I too have a decade long pursuit that I work on as a kind of accretion. In your own Orcadian work, there is clearly a convivial and social aspect to this work; in ‘conversation’ you had in some sense with Mackay Brown, or the intimacy with which you have developed a relationship with his work anyway, and the important friends you have made along the way. That connection with place through its people reminds me of the other body of work I know you for, which is your work documenting war zone and the people affected by it. Can you remind me – was it the Gulf war you were recording? How do you go about brokering those kinds of relationships? Do you see drawing as a way to visit a place and meet its people?

SM: Slow and measured is my natural and preferred state Emma. Taking time over my drawing is a sanctuary. Time enables me to hone in on the muscles and bones of my subjects, to get to know the inner layers as well as the outer and the context within which they sit. I enjoy the research employed prior to starting a project; the intimate knowledge gained spending time working into the drawings and the contemplation of the work post production. That quietens my brain. It takes time to build a relationship with anything, or anyone, to gain deep understanding. I said earlier it had taken roughly eight years to complete the Orcadians drawings, but what I didn’t say was I had desired to make drawings in response to Mackay Brown’s writing for more than twenty before then. To do justice to the beautifully simple and richly visual writing though I felt my technical abilities needed firming up. It was about this time that I rekindled my love for life drawing. You’re right Emma, without Mackay Brown himself (he died in 1996) the closest I could get to know him, and the ‘place’ of his Orkney, was via my own explorations and talking with his friends, but the most accessible method was through his writing.

The other body of work you are referring to is my Memoria Histórica project, where I documented the excavation of a Spanish civil war era mass grave in Valdediós, Asturias in northern Spain in 2003. Although both Orcadians and this project are connected through themes of place, memory and time the making of the Memoria Histórica work was more concrete, tangible in a more emotive sense than Orcadians. The connections and ‘conversations’ were real. They were with people directly affected by this historic crime; sons and daughters of the victims in the grave; witnesses to the immediate aftermath of the crime itself in 1938; and as a demography of Spain’s social history post-civil war the place played host to a gamut of views and beliefs, of anger as well as sensitivity. The excavation was big news nationally. The site was overrun by media, in the form of journalists, film-makers and photographers; on some occasions there was an air of animosity towards them as they scrambled for the best position at the gravesite from family and volunteers. My experience though, as an artist making drawings was one of respectful welcome and fascination. I stood back and was quiet. When I was close to the ‘action’ I stayed put, not flitting from one area to the next. As I respected their space they showed respect for me and my work. They were always interested to see the work as it developed and to see my depiction of them and the scenario that was integral to their personal history. So, to answer your question Emma, yes, along with the concern of respect drawing has a power to fling open the doors and to help forge strong connections with people; perhaps it is our primal relationship with the act of drawing that makes for this familiar bond.

ED: The primacy of drawing – yes, I certainly agree with Deanna Petherbridge on that one. This notion of care and labour comes across very strongly and I like the idea that one’s practice can really be built around oneself. We talk all the time about personal practice, but what does that really mean -it can require resolve to protect and nurture one’s practice, to get to know what a personal practice really entails and stand by it. I hardly dare ask what you are working on as it is rather like trying to gauge the swell of the Atlantic, perhaps you are in a period of deep gestation just now? One of my favourite artists, Ian Breakwell, made a great tv programme about artists waiting and observing. Is there something brewing?

SM: I may work in a measured way but am also impatient and don’t tend to have an unwinding period after a project – I’m not very good at that. I like to have something in mind, something brewing to ‘obsess’ over before completion of the previous project. It keeps my levels of excitement alive.

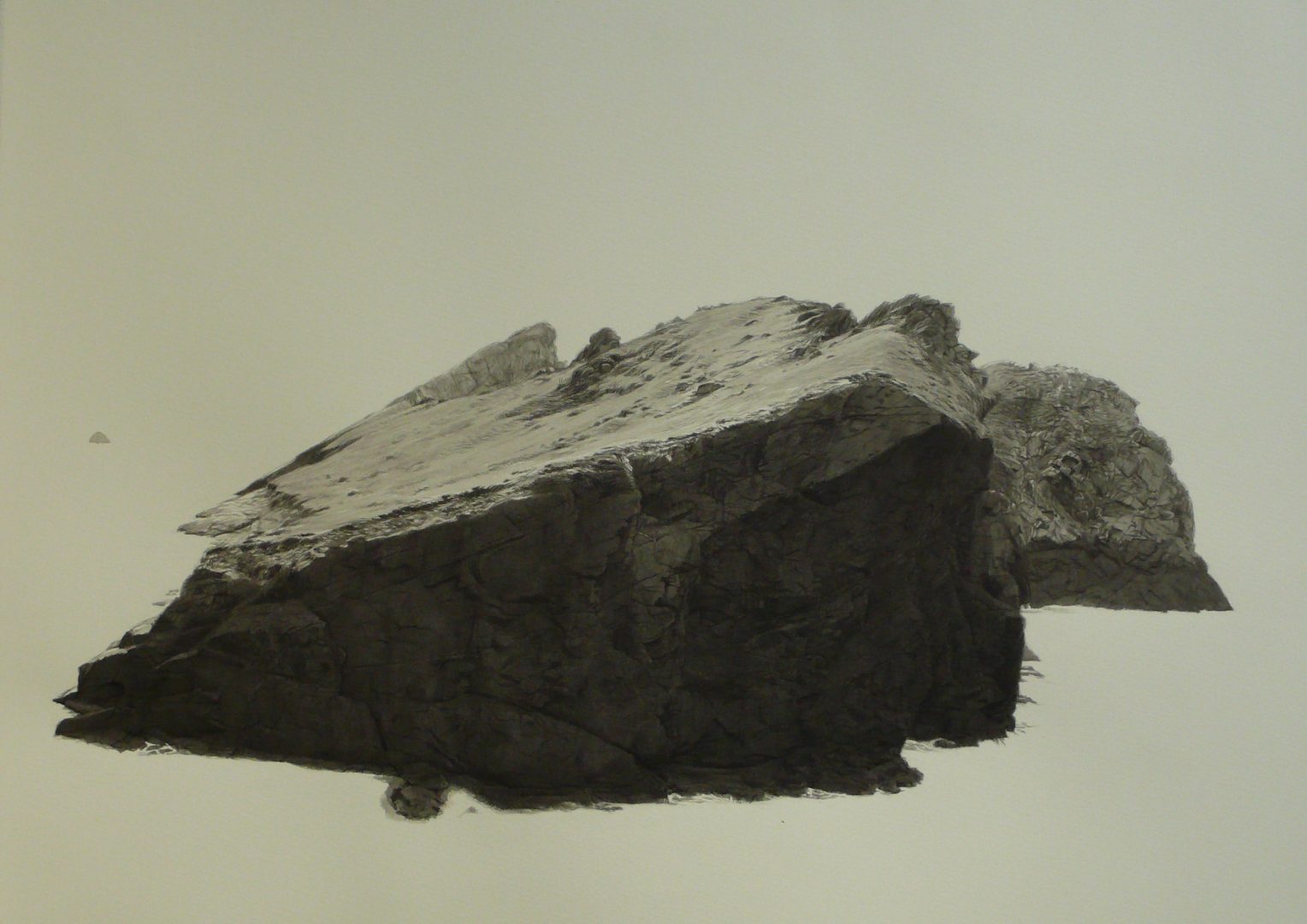

I’m presently working on a series of drawings further exploring the theme of historical memory; this time specifically in relation to our feelings of ‘belonging’ to somewhere. The context within which this project is set focuses on St Kilda, the archipelago fifty odd miles west of the Isle of Harris in the Outer Hebrides, and will consider any fundamental connection felt by the descendants of the thirty-six St Kildans who made the difficult decision to evacuate the islands in 1930 to their familial past. The drawings so far are depictions of the land, isolated and geological, and are taking me in more conceptual directions than explored in previous work.

Alongside the St Kilda project next year I will commence work on a new book commission. This will be a visual response to the poem On a Raised Beach by Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid. MacDiarmid’s long, dense poem will be a useful addendum to the work being explored for the St Kilda project and will allow me to continue investigating this developing visual language.

ED: Thank you so much Simon, I’ve really enjoyed gaining an insight into your creative world and am inspired by your deep and humane understanding of historical memory of place. I’m sure “Personal Approach to Drawing’ students (DR5PAD) will hear echoes of it now as they study.

|

|

I have a question to ask. I am thinking of applying for the open drawing degree at some stage, however I am not sure how to apply. is there any link on this page. Also are these courses really for free, because I thought that was what the front page said but I didn’t expect it to be.

Thank you

Hello David, I’ve emailed you separately so that I could connect you to the student services team. The website address is http://www.oca.ac.uk if you wanted to look more closely at the drawing degree.