What would we do without villains?

One of my students made this perceptive comment in her assignment reflections; Working through the exercises, I also realised I had only thought of all the internal conflicts; however, I have not thought of a definite villain, and I am unsure of whether I want to include one after reading The Gloaming by Kirsty Logan. In The Gloaming, there is not one major external conflict that influences every character. Rather, it is a retelling of life and its unexpected twists. The book made me think of how I want to present the story; do I want there to be a villain to defeat? Or am I satisfied with writing only about their internal conflicts, and their battle with the storm?

Not all stories have a bad guy or gal. Conflict, and the thwarting of desire, can come from many other sources. In fact, having a villain at all could be thought of as an artefact of certain genres; action, crime, romance and adventure, for instance, although for the purpose of this blogpost, I’m casting my net more widely. Some of the greatest literature features ‘the villain’, Shakespeare being master of the purposefully evil human intent on destruction and full of hate, and Dickens taking up that mantle willingly, creating iconic villains such as Uriah Heep.

I asked my student why she was considering the idea of an specific antagonist. Maybe it’s because everyone loves a villain. Characters like Hannibal Lector (from Thomas Harris’ series of thrillers) Nurse Ratched (One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Ken Kesey), or Stephen King’s Annie Wilkes (Misery), have gone down in history to the point their names are synonymous with cannibalism, bad nursing, and fandom obsession. It’s got to be fun to include a villain in your fiction, right?

I wanted to suggest she gives this idea the wide, long view. A villain is only one type of antagonist, after all. Sometimes the protagonist in a story is faced with something that is not even human, such as natural or inanimate forces and events that take on the villain’s role. In The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood isn’t pointing to one individual who is villainous. It’s the state itself, the Republic of Gilead, which sprang from the ideas of well-meaning people to become a monster in itself.

Of course my student doesn’t have to have a villain in their story…but does she need any type of antagonist at all? There are two kinds of antagonist often overlooked, when talking about ‘the bad gal or guy’. Creators of conflict can be antagonistic. Such conflict-generating antagonists are characters with goals and desires in direct conflict with the protagonist. Look at Javert, the police inspector in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Javert’s lack of empathy with any criminal leads him to ceaselessly search for Valjean.

Another kind of antagonist is the protagonist themselves. We all know someone who is their ‘own worst enemy’. Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. is such a one. Holden comes into conflict with almost everyone he knows, because the antagonising conflict is based in his own obsessions and insecurities. In Atonement by Ian McEwan, Briony holds such a degree of guilt internally that her entire life becomes wrapped up in atoning for it.

If you’ve decided to seat the conflict of your story within the protagonist, rather than an external villainous force, a strong backstory will be imperative for fuelling that inner conflict. It also becomes tricky to create defined moments of conflict and the solution often lies giving your protagonist a distinct trait, such as anxiety, anger-management or dissatisfaction with their life. You’ll need a incentivising goal for the protagonist, which is fully hindered by their internal struggle.

Antagonists are often forgotten at the character sketch stage. Villains may remain shadowy on the page for very good reasons, and this is often the excuse a writer gives themselves. However, for a bad guy or gal to be plausible, you need to know them inside-out, especially their motivation and their history. Don’t just expect the reader to assume that the antagonist is evil – end of story. The writer needs to justify them, and know them inside-out, especially their motivation and their history.

Some stories focus on conflicting protagonists. Here we encounter two characters, both taking the protagonist role, each with personally relevant but opposing, or incompatible, goals. Their conflicting struggle will cause them to want to defeat the other, with the reader as onlooker, enjoying the clash, but not specifically invited to root for one over the other. Recent examples are Amy and Nick Dunne in Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, but we’ve seen conflicting protagonists as far back as Pride and Prejudice. Jane Austin shows us how to do this tricky conflict trick perfectly. Both main characters, Elizabeth and Darcy, have too much pride and too high a degree of prejudice, which almost prevents their happiness. Perhaps I’m stretching the description of ‘protagonist’ a little far by including Darcy here, but he is many a reader’s fantasy lover, after all.

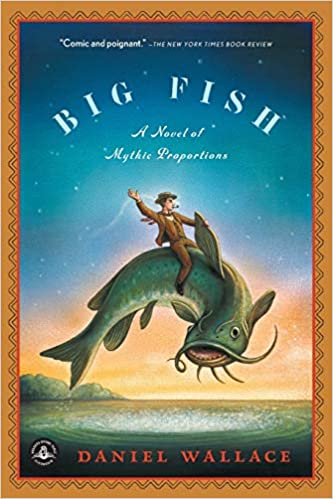

Conflicting protagonists can be wholly benign characters who make their own dramatic tension from almost nothing. In Daniel Wallace’s novel Big Fish; A Novel of Mythic Proportions, we meet Edward, who loves to spin a tale, and William, his son, who is often exasperated by what he desperately doesn’t want to think of as ‘Dad’s lies’.There is conflict between these two because they love each other. If you haven’t read the book, you may have seen Tim Burton’s movie version, where William only comes to terms with these tall tales at his father’s funeral.

It’s possible that what my student really needs, is not a villain, or any type of full-blown antagonist but a contagonist. This term was coined quite recently by Dramatica, https://dramatica.com/dictionary/contagonist, but of course the concept has been around since novels began. Dramatica says…If Protagonist and Antagonist can archetypically be thought of as “Good” versus “Evil,” the Contagonist is “Temptation” to the Guardian’s “Conscience.” Because the Contagonist has a negative effect upon the Protagonist’s quest, it is often mistakenly thought to be the Antagonist. In truth, the Contagonist only serves to hinder the Protagonist in his quest, throwing obstacles in front of him as an excuse to lure him away from the road he must take in order to achieve success. The Antagonist is a completely different character, diametrically opposed to the Protagonist’s successful achievement of the goal.

In Enduring Love by Ian McEwan, Joe, the central character, and his wife Clarissa, become involved with a hot air balloon rescue with four others. One of these, Jed Parry, is so affected by the event that it changes all three lives. Jed offers the tension needed for the story without being in any way villainous. So if there is someone in the background of your prototype story who represents temptation and hinderance, a character who throws damaging stumbling blocks in the protagonist’s way, luring them from any quest or goal they’re aiming towards, you might put dramatic tension in a contagonist’s hands. This character may be benign in aspiration, but would thwart the protagonist, often without knowing they have done so, and certainly without meaning to do so.

What about the idea that fiction can survive without active opposition or hostility from any quarter, human, or not? Can a writer completely do without an antagonist? Even the most worthy literature falls very flat without dramatic tension, and that does have to spring from some kind of conflict, which is usually described as the antagonist, whether this is a supernatural entity, an internal struggle, a jealous lover, or tsunami. Remember the first principle of writing; no conflict, no story.

If you’re not sure about the conflict levels in your story, ask yourself if your protagonist’s goal will seem too easily achieved if you keep the narrative arc as it stands at the moment. If the answer is ‘yes’, you may very well need an additional antagonist – something, someone, somewhat…to force your protagonist to struggle further before they can thrive.

So thank you, Yasmin, for your wonderfully reflective comment which has allowed us to wander among some pretty dark characters without harm to ourselves.

Villains, eh? What would we do without them?

|

|