What I’ve learned from travelling back in time (in short stories)

A few months ago I wrote a blog about what I’d learned from travelling around the world in short stories. In that blog I discussed the value of reading work from other cultures. This time, instead of travelling around the world, I’d like to travel through time, and share what I’ve learned from reading some old short stories.

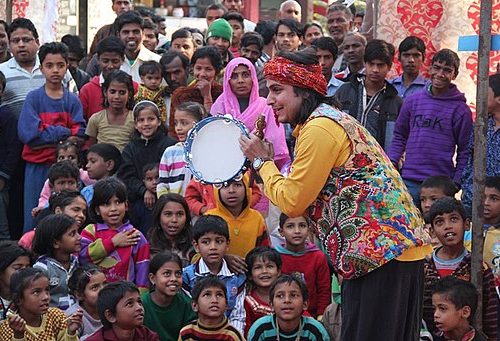

By ‘old’ I mean stories that come from oral traditions – the kinds of stories that would have been told around the fire, rather than designed to be read in a book. Although the oral stories I’ve been reading recently are available in print, they tend to be difficult to date. This is because they aren’t usually unique to an individual author, but are passed down from one storyteller to another, with each person adding, embellishing, misremembering, and making the tale their own. Many are still told today, in cultures around the world.

Think for example about the Grimms’ fairy tales. The brothers didn’t write these stories from scratch, but listened to renditions by storytellers and jotted them down in a form that would make sense on the page. A well-known story such as ‘Hansel and Gretel’, for example, would have existed in German culture long before the Brothers Grimm published it. The same is true of Scottish Border Ballads like ‘Tam Lin’, and of fables such as the traditional Zulu story, ‘Why the Cheetah’s Cheeks are Stained’.

So what have I learned from reading stories from oral traditions? Firstly, oral cultures tend to be fascinated by the overlap between the human and non-human worlds. In the Zulu tale, an old man and a cheetah have a conversation. The Grimms’ story ‘The Goose Girl’ features a talking horse. In the Book of Jonah, a book of the Bible which many scholars think existed in oral versions before it was collected in scripture, the prophet Jonah is swallowed by a giant fish and lives in its belly for three days, until God intervenes and sets him free. In Metamorphoses, a compilation of mythical stories by the Roman poet Ovid, every river and tree is charged with supernatural energy; people and gods frequently change into creatures, plants, and even constellations.

What the tellers of these stories knew, and which we’re only just remembering in the twenty-first century, is that nature and human culture aren’t clearly separated. Our actions affect the non-human world around us, and vice versa. Without worms processing the soil, for example, farming would be impossible, and we wouldn’t be able to form civilisations, with buildings and politics and creative writing courses and time for storytelling. We share the world with other creatures, and the shape-changing, supernatural goings-on in oral tales are a recognition of this.

Another aspect of oral tales is matter-of-factness. Talking animals, divine interventions and metamorphoses are treated as utterly credible. The reader is required to make sudden, jolting imaginative leaps as they learn that all cheetahs have ‘stained’ faces because of the tears of one mythical mother cheetah, or that the goddess Diana in Ovid’s stories turns a group of mourning women into guinea fowl in order to settle a grudge. If you’re struggling to make fantastical elements in your own writing seem believable, you could do worse than to look at how oral tales handle this subject matter.

One of the most obvious aspects of many oral tales is simplicity of language. Originality lies in the storyteller making the story her own by finding a unique perspective, detail or event that fits within the template of a familiar myth or anecdote. Elaborate turns of phrase are unnecessary, and tend to get in the way of the storytelling. There is power in this simplicity.

Perhaps these reflections on oral stories seem quite remote: these tales come from cultures very different from yours. However, the final thing that struck me as I read old, oral stories was how often storytellers took their bearings from the world around them. Moral lessons were passed on through examples from nature. Readers of Jonah are reminded of the danger of the sea. In Metamorphoses, the fragility of life is made clear through the capricious interventions of the gods.

So let me leave you with a challenge. Are there aspects of the world around you which could inspire a fable? Maybe you don’t live near cheetahs or talking horses, but are there aspects of your everyday surroundings which have the potential to be fantastical?

Image: Kabuliwala storyteller by Prtsh24, Wikicommons creative commons licence

|

|