Creating great character voices: Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible

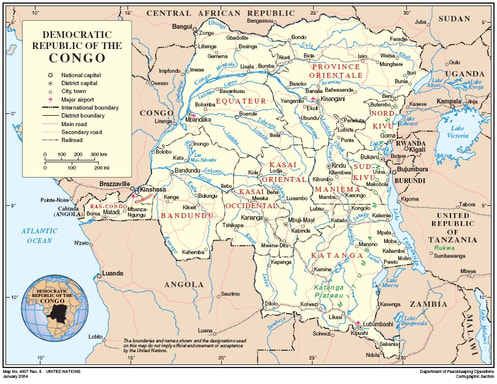

In Barbara Kingsolver’s fourth novel, The Poisonwood Bible, (1988), we see the Price family carry everything they need onto a lumbering 1950’s plane and fly to the Belgian Congo to take up a missionary post in a village called Kilanga on the Kwilu River.

Creating the voice of characters who feel realistic, authentic and engrossing is one of the most difficult parts of writing. Kingsolver says,… “Good fiction creates empathy. A novel takes you somewhere and asks you to look through the eyes of another person, to live another life. Literature sucks you into another psyche. So the creation of empathy necessarily influences how you’ll behave to other people…” It is, she adds, a “powerful craft; there’s alchemy…”

She has created five independent and distinctive voices within this book. Each female member of the family narrates their story in turn. The magic trick Kingsolver achieves as a writer is to make their voices entirely original and independent of each other. When I read the book, this was the remarkable thing that struck me hardest. It was as if Kingsolver truly knew the five women whose stories she will tell.

Orleanna married Nathan Price when she was seventeen and gave birth to three children in the space of two years. As they are shunted about the missionary world, she loses her spirit. By the time we meet her, it seems to me she’s entirely a passive vessel for her husband’s will – although she hates the Congo.

…First, picture the forest. I want you to be its conscience, the eyes in the trees. The trees are columns of slick, brindled bark like muscular animals overgrown beyond all reason…The breathing of monkeys. The glide of snake belly on branch […]The forest eats itself and lives forever…

Rachel is her first-born daughter, an unadulterated egomaniac, just as her father is, except she’s focused on the state of her appearance and her comfort, not her soul.

.…we stepped off the airplane and staggered out into the field with our bags, the Congolese people surrounded us – Lordy! – in a chanting broil. Charmed, I’m sure. We got fumigated with the odor of perspirating [sic] bodies. What I should have stuffed in my purse was those five-day deodorant pads…

Only slightly younger, and very gifted, are the identical twins, Adah and Leah. At birth, the left side of Adah’s body was paralysed. She limps and is almost speechless, but her mind is acute, and it’s through her voice that a considerable amount of the book’s political scenes are related.

…Our Father, who now made a point of being home to receive Tata Ndu, would pull up one of the other chairs, sit backward with his arms draped over the back, and talk Scripture. Tata Ndu would attempt to sway the conversation back around to village talk, or to the vague gossip we had all been hearing about…but mainly he regaled Our Father with flattering observations…

Compare this voice with that of Adah’s healthy twin sister, Leah…

I prefer to help my father work on his garden. I’ve always been the one for outdoor chores anyway, burning the trash and weeding, while my sisters squabbled about the dishes and such. Back home we have the most glorious garden each and every summer, so it’s only natural that my father would bring over seeds in his pocket…

Ruth May is the youngest of the sisters, nine years junior to the twins. She is an impish child and Kingsolver concentrates on penetrating the little girl’s mind, so that, although her thoughts are lisping and playful, we can glean a lot of the story’s subtleties from her…Sometimes you just want to lay on down and look at the whole world sideways. Mama and I do. It feels nice. If I put my head on her, the sideways world moves up and down. She goes; hth-huh. hth-huh. She’s soft on her tummy and the bosoms part…Sometimes I tell her; Mommy Mommy. I just say that. Father isn’t listening so I can say that…

On her website (see the link below), Kingsolver reveals how she was able to write so convincingly in five different voices: “I spent nearly a year getting the hang of the Price girls, by choosing a practice scene and writing it in every different voice. I did that over and over until I felt the rhythm and verbal instincts of character: Rachel’s malapropisms, Leah’s earnestness, the bizarre effects of Adah’s brain damage, and so forth. Adah was the most challenging character I’ve ever created, starting with a lot of medical research about hemiplegia.”

Writing in many voices within one novel is a challenge, one that can demonstrate a writer’s prowess, as it does here, but one that can fatally wound a promising idea for a story, weighting it down, making it over-complex, and pushing a student writer’s skills to the very limit. It is not a choice for the faint-hearted…or the beginner, which is why at HE4, in the Starting a Novel course, the course materials strongly advices the student to stick to one narrator.

But if you want to see a master at their work, this is a book that can show you those skills. The Poisonwood Bible is about so much more than the secret interior worlds of its female narrators. For Kingsolver, it is an “allegory of the captive witness. We’ve inherited this history of terrible things done, that enriched us in the US and Europe by pillaging the former colonies. How we feel about that is the question in the book.”

Go to Kingsolver’s website to find out about this, and her other books; http://www.kingsolver.com

|

|