Documentary evidence and artistic expression.

Exhibition: Empire of Memory at ‘Temporary Contemporary’ Huddersfield, January 2019.

As a photojournalist I grapple with a number of problems: can a realistic medium such as photography ever really show the underlying causes of social problems? A mechanical recording instrument has a limited capacity to convey a point of view, or express an author’s emotional response. How might we picture subjects that almost can’t be photographed, such as personal history, the memory of an absent loved one or the big themes such as poverty and war? These paradoxical problems are not new. In the 1930s the playwright Bertolt Brecht, exclaimed that “less than at any time does a simple reproduction of reality tell us anything about reality”. He argued that in order to confront the audience with uncomfortable truths, the artist had to ‘show that he was showing’ by making the process of representation explicit, thus revealing these relationships as constructed. Could re-purposing documentary photographs by placing them in an art gallery context, question this notion of the news event as an accurate record of social history and thereby force a change in the condition of the viewer?

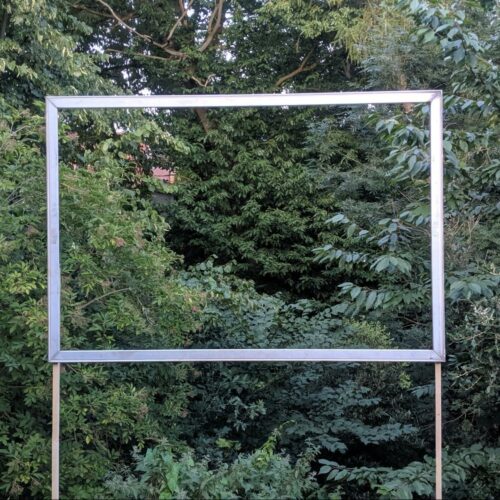

Empire of Memory: Post War Remembering and the Archive is an attempt to collate disparate photographic fragments using novel strategies to prompt a debate on memory and the representation of war and conflict. ‘Temporary Contemporary’ places art in vacant spaces within a market in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire. It is an interdisciplinary, collaborative initiative which also acts as a testing ground for experimental ideas from researchers, artists, designers and businesses but also has a remit to appeal to a wide spectrum of visitors.

Prompted by a commemorative coin bequeathed to me by my father, a memorial to his own grandfather who died at the onset of the First World War, I began to consider that conflicts in many instances may be fought in the memories of citizens rather than on actual battlefields and, as such, require alternative approaches to their visual depiction. Looking though my archive I began to notice radial reverberations of recurring events which echoed those of previous conflicts. In my great-grandfathers time, this was largely a war springing from disputed borders or struggles over scarce raw material resources and arguably, also promoted by the powers that be in order to control and divide people. In the present, it is ideology, a clash of beliefs – Islam v ‘The West’, nationalism v immigration, the after effects of domestic terrorism; the resurgence of far-right dogma; even the recent Brexit, could be conceivably, a conflict over fictional myths and symbols of nationhood. The historian Margaret MacMillan, alludes to these echoes from the past resurfacing in the present, referring to Mark Twain’s observation that: “History never repeats itself but it rhymes”. Commemorations, anniversaries, and recollections of past wars re-frame present day conflicts. Photographing chance events, sudden catastrophes, even everyday political disputes could be seen as an echo of accidents from a previous era.

Following last years centenary of the end of the First World War, I began to photograph commemorations and memorial rituals as a first stage response to this idea of post-war remembering ‘handed-down’ from generation to generation as a form of haunting. In turn, I also drew from my own archive of news protests, for example, the liberation/invasion (depending on how one looks at it) of Iraq and the patriotic/nationalist protestors at the cenotaph in Leeds (where I now live) and nearby Bradford (where I was born).

When covering these events as a commission, I always have a film camera to hand. In the annual Remembrance Sunday event in Bradford using a 5 x 4 large format camera and then returning to Leeds to take a quick snap on my Mamiya 6. Here I noticed several shops displaying the iconography and recurring motifs of war remembrance such as poppies, flags and – in an ironic Eugène Atget style – a rendition of the unknown soldier through the window of a charity shop in Headingly. These photographs were often an afterthought, not worrying about making a ‘professional’ picture but serving as an aide-memoire to what I could see were different – often opposing – images of what the remembering of war entails: the gravity of my great-grandfather’s still life ‘brave life given’ official token of remembrance; a patriotic veteran walking away from the cenotaph; to a poignant throwaway reminder of ‘memorial as commodity’ reflected in the shop windows of Leeds.

Another historian, Jay Winter uses the term ‘historical remembrance,’ to define these sites of second-order memory, as metaphors where competing narratives ‘collide’ “out of the different subject positions of those involved.” In the last shop window, a jewellers with poppies laid out like a shroud underneath the glittering costly timepieces, a flash of light on the edges as light accidentally leaks into the last frame of undeveloped film. Similarly, whilst recording memorials closer to home and forgetting to turn the dark slide of the Linhof 5 x 4 around, I accidentally double exposed a nearby war memorial with an earlier view from the window of my house at the council flats opposite. This ‘Dadaesque’ forced juxtaposition of poppies and social housing, with the just visible cross of St George in one of the windows becomes a prescient reminder of what became of the returning soldiers after the horrors of the First World War. They expected their life would return to some normality, in a secure and safe environment and jobs for all as the then Prime Minister, David Lloyd George apparently promised them ‘homes fit for heroes.’ What he actually said was: “Habitations fit for the heroes who have won the war”, not the phrase everyone believes they remembered. The word “habitations” suggesting something much more prosaic and basic. Unable to fit the exact phrase in a sentence of a newspaper column header, it was conveniently shortened to the phrase we have come to know.

Even in news reporting then, history and memory are selective but also constructed: representing these abstract ideas makes a distinction between personal affective (i.e. emotionally responding) memories and the social effects of official remembering. As John Berger in his Uses of Photography, remarks, this relationship of individual personal memories with that of the wider societal collective memory, isn’t linear but spread out like light rays, diverging in lines from a common centre, analogous to both the way history works and also to the way photography is used to construct knowledge. He argues that if we wish to place the photograph back “in the context of experience“ of social memory, (he returns to a quote from Brecht), one should “make the instant stand out but without hiding the process by which it stands out”. Adopting this idea, I decided to make it obvious that these events were fixed by a mechanical recording device open to unintended consequences, not via a transparent ‘window on the world’. These chance accidents emerging on film have disrupted the seemingly self-evident outline of official history.

Printing the images large in the gallery and including hand written marks (how we used to indicate preferred negatives to be blown up) is a way to show the process of selecting significant moments (as historians also do) from the possible outcomes available. Allowing the unique properties of film photography: jammed mechanisms, accidental double exposure, marks of chance light leaks, allude to the ‘after-shocks’ and reverberations of war in the present day. These were viewed differently by the diverse audience attending the gallery. Professional photographers expressed an unease at seeing prints simply nailed to the wall with curled edges at the base. One of the market stall holders remarked on the strip showing the wreaths from different religious groups and the ‘pro patria’ inscription ( from the poet Horace translated as: ‘It is sweet and proper to die for one’s country’) and said: “its a shame you ran out of film…” – there are 12 frames on medium format film but I still managed to somehow squeeze a 13th frame, until the angel flared out. My father, was pleased to see his own father’s old super 8 films projected on the wall alongside a picture of himself, depicted in a commemoration service for war heroes but only remembered the child holding a white ‘peace poppy’ after the event; when alerted by the yellow selection marks on the large three frame print. These shifting settings where photographs are looked at means making sense of the world isn’t dependent on what the picture literally refers to but on perception: the potentially conflicting ideas or feelings the picture invokes in a viewer. This meaning is different for differing people and groups of people as they remember events; or images of those events, many years later.

Questions, such as: what do we believe in? Why do conflicts keep recurring? What does it mean to be a man? Personal responses can assess these collective memories of a nation and may persuade us to consider our own role in the process of reflection and possible healing. As Margaret MacMillan states: “ if we can see past our blinders and take note of the telling parallels between then and now, the ways in which our world resembles that of a hundred years ago, history does give us valuable warnings”.

I would like to thank Professor Donal Fitzpatrick at the University of Huddersfield; Fionna Barber and Dr Andrew Warstat, Manchester Metropolitan University for their help and advice in the production of this exhibition and article.

This article is an updated version of a presentation given at the 2018 Pictures of War: The Still Image in Conflict since 1945 conference at Manchester Metropolitain University 24 – 25 May 2018. Download the Programme (PDF) here.

Empire of Memory Post-War Remembering and the Archive project and exhibition can be viewed on Garry Clarkson’s website: http://www.garryclarkson.com.

Temporary Contemporary Market Gallery Huddersfield, exhibition initiative can be seen here.

Further References:

Bertolt Brecht’s quote ( “less than at any time does a simple reproduction of reality…”) is used by Walter Benjamin, (1931) in his Little History of Photography, Die literarische Welt,(Gesammelte Schriften, II), 368–385. Benjamin also proposes aesthetic ‘shocks’ to promote the ‘reification of human relations’.

Margaret MacMillan (2013), The Rhyme of History: Lessons of the Great War. Brookings Institution Press. can be read here.

Eugène Atget was a photographer acclaimed for his determination to record the architecture and street scenes of Paris before their disappearance. He was taken on by the Surrealists as an example of how photographic documents might be re-used in the service of art. Walter Benjamin’s writings were greatly influenced by Atget’s images during the 1920s and 1930s. See MacFarlane, D. (2010). Photography at the threshold: Atget, Benjamin and Surrealism. History of Photography, 34(1), 17-28.

- Atget’s window pictures such as Magasin, avenue des Gobelins 1925 can be seen here.

Jay Winter, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History, Cambridge, 1998.

Dada an ‘anti-art’ movement formed during the First World War as a negative reaction to the horrors and folly of conflict, included techniques such as cut up collages, photomontage, assemblages and readymades. See here.

Homes Fit For Heroes and Lloyd George’s promise is considered by Martin Stilwell in his Early History of Social Housing in Britain, here.

Bill Brandt’s portraits from an assignment for the Bournville Village Trust reveal these contrasts between slum and municipal housing and the living conditions of the working classes at the time of the Second World War. Brandt, B., James, P., & Sadler, R. (2004). Homes Fit for Heroes: Photographs by Bill Brandt, 1939-1943. Stockport: Dewi Lewis in association with Birmingham Library Services.

John Berger, in The Uses of Photography, quotes a passage (“you should simply make the instant stand out” ) from Brecht’s Portrayal of Past and Present in One, (1938), in The Messingkauf Dialogues. Trans. John Willett (1965), Brecht’s Plays, Poetry and Prose Series. London: Methuen.

Dulce Et Decorum Est Pro Patria Mori – by Horace was used by war poet, Wilfred Owen in a different context, discussed by The Poetry Society here.

Gallery Display of printed large contact prints, including edges and negative numbers necessitates having the original negatives drum scanned (on a machine that can cost up to £100,000!) This is apparently a difficult process as scanning to include all of the rebate can cause problems with autofocus. Professional Drum Scanning is a boutique photography business run from a design studio in Ballachulish, (near Glencoe) in Scotland. My thanks to Tim and Charlotte Parkin for their invaluable help with this process. see: http://www.drumscanning.co.uk

All Images © Garry Clarkson

Arthur Clarkson, (3rd May 1910 – 18th Feb. 1974), Super 8 film c. 1968 and archive photographs can also be seen here

Empire of Memory Video Installation. from G-Film on Vimeo.

Featured Image: Garry Clarkson, Empire of Memory, Market Gallery (Temporary Contemporary), Huddersfield, UK 26 January 2019.

I’m reading this a few months late but it’s relevant to an essay I’m writing about photography and memory, so I have some belated observations… The Berger references about how memory works ‘radially’ and the interplay between personal and collective remembrance links into some research I’ve been reading (Dudai & Edelson 2016) about ‘interpersonal’ memory and the potential leakage between experienced memories and those socially ‘absorbed’. So there’s another Berger quote going into the essay 🙂

But for me the most fascinating thing about this post, for various reasons, was the use of vintage-tech equipment. Firstly, the very act of walking around with a large format camera in the 21st century is an act of memorialisation, which imbues the work with a ‘past-ness’ even when taking pictures of contemporary scenes, and this combination of past and present is analogous to how human memory works. Secondly, the whole concept of ‘showing the process’ can be achieved more successfully with analogue photography than with digital as it produces physical evidence of the process, including errors and glitches; so the medium supports the message. Finally, large and medium format photography’s limited number (and cost!) of achievable images makes me think that photography in the past was a *much* more selective act, with the photographer taking more time and discernment in choosing when to press the shutter – which in turn makes me wonder how ‘pre-edited’ much analogue photography was, and so how much of history was ‘missed’, if that makes sense.

So the decision to use large and medium format cameras for this work is, I think, a big part of why it works.

You could have written the exhibition introduction 🙂 Have you read Joel Colberg’s book on editing the phonebook? He remarks that we should practise selecting from small prints (rather than on screen) and ‘live’ with pictures. Snapshots are edited for story after the event but one of the special conditions of large format (due to size, cost and time taken to compose and think about what’s in the picture much more) is that you are editing in the camera rather than on a table after the event with hundreds of 6 x 4 prints. Investigating as as you are framing. Its slower but more meditative. “Photography is editing, editing is Photography” could also be analogous to memory. I obviously ‘edited’ these memories and meditations on the semiotics of national identity. Thanks Rob for a productive dialogue.

J. (2017), Understanding Photobooks, The form and Content of the Photobook, Focal Press.

Coming to this late from viewing the images on https://www.garryclarkson.com/empire-of-memory, the first thing that strikes me is the idea of shared memory encompassing numerous generations. The people who experienced these Wars are nearly now all gone, yet still WE remember.

A social construct decided upon in order to try and stop history repeating itself. Our opinions guided by images we have seen and stories we have heard. The idea that you, in turn, are creating a second generation of images, if you like, to strengthen this memory, using the same equipment and technique that my grandfather would have used creates a stronger bond with the image than if it was simply digitally captured. The physical photograph being somehow more real, than pixels on a screen. The effort required giving rise to a stronger memory bond with the event itself.

As the generations involved or with a direct connection pass, the future generations will rely more and more on imagery and passed down stories to have the same connection we may have to, not the events themselves, but the shared feelings about them. Images showing people coming together 80 or more years after the event to remember will start to become more important, as these are now our actual memories, the acts of remembrance.

My strongest memory of this, is as a child, my grandfather showing me pictures from the war. A number of 6×4 images perfectly composed and photographed, of his time in a POW camp after the fall of Dunkirk. All were cheerfully posed, playing in bands or sports of some kind, resting in the sunshine, eating and drinking, or sharing a joke with a guard. Sunny Days in Stalag 8b, he said, bitterly. It was only later he showed me these were propaganda images, officially stamped on the back by a German officer. Other images were not quite so jovial and considerably darker, images that still today I find hard to look at.

I mention this as without his story, his witnessing of events, the images could easily create a false story, leading in time to false shared memory. This is the power a photograph has, people believe what they see, more so than what they hear. Isolated moments in time with little or no external context are easily used to manipulate. As you say above… ‘the potentially conflicting ideas or feelings the picture invokes in a viewer. This meaning is different for differing people and groups of people as they remember events; or images of those events, many years later.’

Well put Sean. Lovely message. These ideas (from Marianne Hirsch) of ‘post-memory’ and the African Zula therapeutic ideas of ‘Family Constellations’ – given to me by OCA tutor Matt White I believe have driven this work – as I attempt to visualise a dynamic that spans multiple generations and via civil engagement (in exhibition etc) try to resolve the damaging effects through representation and ‘materiality’ of things and images that encounter and accept the grim factual reality of the past. See you soon.

Reading this has coincided perfectly with completing the Level 2 Module Challenging Genres and this article is exactly that, how you have used your artistic expression to challenge the notion of the documentary photograph as representing reality. This is what I have taken from this very complex exhibition and your commentary.

The two phrases in the title are in opposition to each other ` Documentary evidence` and `Artistic Expression` and give a clue about the content of the article and the exhibition.

The exhibition uses the context of memory and remembrance of war. Our memories are already selective and subjective and if our knowledge of wars that we have not lived comes from photographs it is very important that we are aware that they are not the whole story and reconsider what is it that we really ‘know` and `remember` collectively. This is not just true of past wars but is even more important today when governments want us to support their wars. The images that we see in newspapers, online, and on the `News` present us with partial truths, we do not get the whole story.

Documentary evidence refers to how the documentary photograph from the earliest days of photography has been seen as depicting reality, a window on the world, objective. Evidence connotes scientific/fact. On the other hand, artistic expression is what artists do, they use strategies and techniques to say something about the world that concerns them personally. We accept these images as subjective and what we expect to see in an art gallery.

I discovered that the Brecht quote, that the artist must “show that he was showing” refers to Brecht’s desire to confront the viewer with an uncomfortable truth, for the viewer watching his plays to know that they were watching a play objectively. This stops them from becoming subjectively drawn into a story. He achieved this by breaking the 4th wall, the actors would break off what they were saying and speak to the audience directly or hold up a placard. The audience became active participants rather than passive observers i.e. he made the process of representation explicit. The audience then was in no doubt that they were watching something deliberately constructed, not a story that could be true.

I can see how you have used this technique in the exhibition. The uncomfortable truths here are that what we remember may not be true and that the photographs that we look to, to help us remember may not be what we think they are. It is of course important to remember those who died but have we forgotten the horror and misery of their deaths? Maybe people are haunted by it and find it too difficult to deal with, preferring to justify their ancestor’s death as something noble and brave. Although many of the photographs look like traditional documentary images, the people gathered around the war memorial, and the dignified veterans, several artistic techniques have been used to challenge the viewer to see these images differently. The yellow selection marks on the three-frame print have highlighted to the viewer that the photographer had a say in choosing which image to highlight or blow up, why this one, not that? A subjective decision on the part of the photographer, the little girl carrying a white poppy, is the photographer using his artistic expression to say, what about peace?

The accidental multiple exposure which appears surreal challenges the viewer to reconsider the photographic process as merely mechanical/infallible. Your use of Dadaesque to describe the image emphasises the antiwar sentiment, I was going to say your anti-war sentiment, but we are all anti-war, aren’t we??

The fact of presenting these photographs in the context of an art gallery also challenges the viewer to consider whether, if they are art can they be a realistic reflection of the world? These say to the viewer, that these images are accidental, chosen, and therefore not reality, how do we know the others are not also subjective and do not represent reality?

Given what is happening in the world right now, it has never been more important for people to be more skeptical about the images that are presented to them.