Beeple’s ‘Everydays’: The Value of Digital Artwork

Last week an artwork sold at Christie’s Auction House for $65m (about £47m). ‘Everydays: The First 5,000 Days’ by the American artist Beeple (better known to his family as Mike Winkelmann) is now the most expensive piece of digital art ever created, but its provenance and value are not contained within the work itself, as it only exists as a digital file and has no tangible physical reality. Similarly to many artworks, its value really resides in its documentation, usually a paper Certificate of Authenticity, but ‘Everydays’ exists as a ‘non-fungible token’, or NFT, a digital collectible that records the details of the artwork on a digital ledger known as a blockchain. So, in this case, the documentation is the artwork.

The sale prompted the latest instance of what is an occasional British tabloid newspaper story expressing how absurd they consider the art world to be, a story as old as the tabloids themselves, but occurring in recent times in 1972 with the purchase by the Tate Gallery of Carl Andre’s minimalist sculpture ‘Equivalent VIII’ (forever to be called ‘The Tate Bricks’), moving on to an exhibition including used sanitary towels (‘Prostitution’ at the ICA in 1976), and thence to Andres Serrano’s infamous 1980s photo work ‘Piss Christ’, Damien Hirst’s dead shark, Marcus Harvey’s painting ‘Myra’, Martin Creed’s ‘Lights Going On and Off’ and, most recently, Jeff Koons’ ‘Bouquet of Tulips’ and Banksy’s ‘Shredded Girl with Balloon’. Andre’s work aside, all of the other pieces are what are known as ‘gestures’, artworks that turn on a conceptual flourish rather than the product of years of gruelling pain and effort in a traditional artists’ studio.

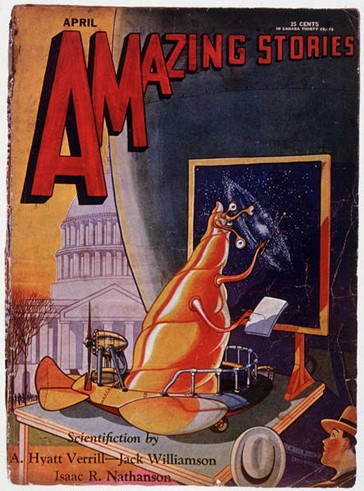

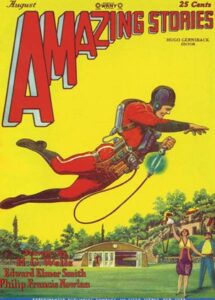

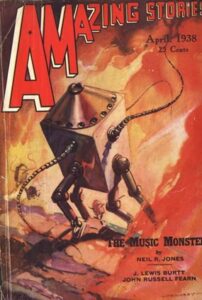

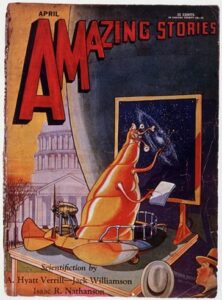

Every few years these conceptual gestures enrage a tabloid press perpetually seeking to support their stereotype of cynical artists duping the gullible gallery curator and high-spending art collectors who can all then be presented to the general public as ‘folk devils’. However, it’s the visual content as much as the newness of its delivery system that makes Beeple’s ‘Everydays’ different to previous artworks by artist/showmen. To create his collage, Beeple made a digital painting every day for 13 years (hence the title), and the pictures themselves are highly accomplished photo-realistic renditions of futuristic landscapes, dystopian visions and otherworldly scenarios, the types of imagery more familiar from computer games and heavy metal album covers, artforms ordinarily reviled by the fine art establishment. This style of imagery has a long but mostly checkered existence, beginning nearly 100 years ago with the first issue of ‘Amazing Stories’, an American science-fiction ‘pulp’ magazine, so-called for the cheapness of its newsprint stock as opposed to the more upmarket ‘glossy’ publications printed on shiny coated paper. ‘Amazing Stories’s painted covers visualized the text stories contained inside, and condensed these narratives to what became known as the three principal visual components of ‘rockets, rayguns and robots’. From the success of ‘Amazing Stories emerged hundreds of imitators, and from the 1920s to the 1950s these publications’ covers were completed by artists who often possessed a classical art school education but needed to make some quick money; according to the wife of ‘pulp’ artist Norm Eastman, his paintings were “hidden under the bed or closet, and were done to afford a loaf of bread and peanut butter to eat.”

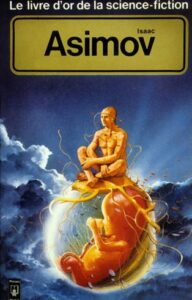

These stock visual tropes continued unchanged through to the 1960s, when they were extended by the hippie-era consumer to wrap the mass market paperback books of writers like Michael Moorcock, Isaac Asimov, Ursula K Le Guin and Philip K Dick and the vinyl records of progressive rock bands like Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer. In the 1970s the familiar imagery by fantasy artists like Chris Foss, Roger Dean, Moebius and Patrick Woodroffe began to be collected in coffee table editions and the pages of ‘slick’ French magazine ‘Metal Hurlant’. The ‘cyberpunk’ literature of the 1980s upgraded the visual language with the incorporation of man-machine hybrids, while the gothic ‘steampunk’ movement added Victorian stylings to the vernacular form. More recently, American ‘lowbrow’ painters like Robert Williams and Todd Schorr have expanded the visual vocabulary in their magazine ‘Juxtapoz’, while artist Jim Shaw created his 170-picture narrative ‘My Mirage’, a mindboggling collection of pastiches of American poster art, comic books, rock album and religious tracts that tells the semi-autobiographical story of childhood and adolescence in 1970s Michigan.

Which brings us to ‘Everydays’, where the visual echoes of all the above cultural artefacts can be seen in its impressive compendium of sci-fi stylings. The non-existence of the work is a complete contrast to the very physical form that its century-long cultural antecedents have taken, with their image influences from magazines, comics, books, records and paintings distilled into metadata. But for all its kinetic intensity, ground-breaking ephemerality and technological modernity, ‘Everydays’ is still an oddly old-fashioned looking artwork. But then, as film critic Richard Corliss once observed, “Nothing ages so quickly as yesterday’s vision of the future”!

|

|